By Silvio Santarossa, Partner Risk Advisory Services, Jean-Pascal Kretz, Senior Consultant, François-Xavier Duqué, Managing Consultant and Kristian Lajkep, Regulatory Compliance Officer

Basel III – Past, Present and Future of the Banking Reform

In December 2017, the Basel committee of Banking supervision (BCBS) published a pivotal document titled “Basel III: Finalising post-crisis reforms”. This paper concerns mostly counterparty credit risk and operational risk, but touches on other types of risks as well. With other types of risks being addressed by other documents in the past, this paper is the final piece of the puzzle. It does not constitute the end to the string of bank regulations - there is no end to regulatory efforts of supervisors, nor will there ever be - but it is a finalization of one of the biggest regulatory projects to date.

This document ended a complex review of banking risk management regulation that was motivated by the regulatory failures exposed by the 2008 crisis. It is the intention of Finalyse to inform you on all major aspects of this review. Since the scale of the changes is considerable, in this paper, we limit ourselves to Counterparty Credit Risk (RWA), Market Risk (FRTB) and Interest Rate Risk (IRRBB) with operational risk coming up in a future release.

It should also be noted that none of the rules published in this paper are legally binding yet. The rulebook pub- lished by BCBS has to be translated into national (or in our case European) law. Whilst there has already been a proposal for the European Regulation (CRR 2) in November 2016 that would incorporate the FRTB and IRRBB, legislators could not keep up with the new releases by BCBS and a new, more complete proposal that also contains the changes from December 2017 is yet to be made.

It is a known fact that the European regulators do not always follow the Basel rules word by word. The EU regulation encompasses more institution that the Basel rules dictate. On the other hand, European rule makers are also putting out a significant effort to make sure that the new regulation does not impede - or impedes to the lowest possible degree, the growth of the European economy.

RWA under the revised Basel III framework

The story thus far

It is no secret1 to the Basel Committee that the Basel II regulatory framework did muster quite a bad reputation as an efficient means to strengthen the resilience of banks, in particular during and after the 2008 financial crisis.

Indeed, the initial framework was somewhat flawed; with the benefit of hindsight, ‘obvious’ issues were overseen. Risk weights did not always adequately capture the risks inherent to their corresponding assets and certain institutions proceeded to amass these assets in a form of regulatory arbitrage, losing among others the benefits of a proper diversification of risks. When the tail risks on the assets eventually realised, many an institution found themselves exposed, particularly to these assets.

Basel III, and its latest iteration, “Basel III: Finalising post-crisis reforms”, aims at getting rid of perverse incentives that the former way of calculating RWA created, whilst still making sure that institutions hold an adequate capital level against their credit and counterparty risks.

In this section we will turn our attention to Credit Risk in particular. It has been long expected that Credit Risk would be massively impacted by Basel 3.5, presented with the stated objective of tackling all the perceived issues of the previous versions and ensuring a level playing field as much as possible; indeed, the current regulation totally overhauls the way risk weighted assets (RWA) are calculated.

1. The most obvious cases of awareness are for instance the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision identifying “mechanic reliance on external ratings” and “insufficient risk sensitivity” as two major weaknesses of the Securitisation Framework in their December 2014 ‘Revisions to the securitisation framework’, or the October 2013 Discussion Paper on ‘The regulatory framework: balancing risk sensitivity, simplicity and comparability’.

Standard Approach to Credit Risk: the new benchmark, with increased granularity

The Standard Approach now sees its granularity and risk-sensitivity increased:

- residential mortgages, with the introduction of Loan to Value as the primary driver for risk weights and a differentiated treatment for residential retail based on whether the repayment is driven by the cash-flows generated by the purchased asset (Income Producing Real Estate treatment)

- recalibration of risk weights for some rated bank and corporate exposures with draft guidelines for jurisdictions unwilling to rely on ratings or exposures for which the rating is not readily available instead of the previous flat risk weight

- specific, preferential risk weight for exposures to small and medium sized enterprises

- specific risk weight treatment applied to equity or subordinated debt

- exposures to project finance can use the generic corporate weights if an issue-specific rating exists and is permitted. Otherwise, weights will depend on the project phase, from 130 to 100 or 80% in pre-operational or operational phase respectively

- exposures to object and commodity finance can use the generic corporate weights if an issue-specific rating exists and is permitted. Exposures will be submitted to a risk weight of 100%.

- credit conversion factors for off-balance sheet items are dependent on the nature of the commitment, from 10% for unconditionally cancellable commitments to 100% for direct credit substitutes, while still allowing for granularity for shorter-term commitments or transaction related contingent items.

Additionally, the Standard Approach becomes the benchmark against which all Internal Rating Based approaches will be measured via the phased-in capital output floor, set between 50% in 2022 and its final level of 72.5% in 2027. Any capital requirement below the threshold will be adjusted upwards to at least the level in force at the time. Banks will also be required to disclose their risk-weighted assets based on the revised standardised approach.

Considering an old favourite from European Banks, mortgage financing, the implementation of the floor will be impacting certain countries more than others. Swedish and Danish banks, followed by banks in the Netherlands, have low historic default rates and extensive advanced modelling approaches, which resulted in lower risk weights.

This partly explains the long-lasting stand of certain countries to call for the lowest possible threshold. However, with things as they are now, the floor might prompt a new move for financial institutions; the race for the most efficient internal model or the tightest levels of risk parameters is momentarily called off, to enable them to find the optimal capital allocation under the standard approach.

Such an optimisation is possible by acting on multiple levers simultaneously:

- Perfecting the implementation of the current exemptions or rules – e.g. preferred risk-weight treatment for SME lending in the RWA calculation

- Increase Data Quality: identify and close old accounts or unused products, ensure completeness of ratings when required

- Either with the simplified or comprehensive approach, make better use of collateral as a credit risk mitigant

- Strategic allocation of resources to minimize risk-weights based on current portfolios, including stepping out of certain activities, or to limit allocation to less profitable business lines

This will allow banks under the Standard Approach to optimize their position in the market, possibly gain access to markets which would be abandoned by more advanced players for which the capital charge increase is too high, and it will allow advanced institutions to ensure their relative floor is lower. However, this theoretical situation has to be taken cum grano salis; of course, every institution is acutely aware that data quality is the key to low capital consumption. Over the last years, data improvement has led to decreases in the risk weighted assets by an average of 10%. From an operational perspective, though, estimating LTV at the origination of older loans or having the information about the final use of the property (own house, buy-to-let, etc.) can prove quite complex, if not impossible.

Internal Rating Based Approach: heavily modified

Past IRB frameworks yielded quite a few weaknesses, encouraging a form of creativity over formal statistical robustness and lacking a minimal set of unifying rules and approaches. These days are now over.

Floored inputs

The new Regulation makes sure that the risk parameters used in internal rating based RWA models cannot be below certain input levels. The input floors for the bank-estimated IRB parameters include:

- PD floor for both foundation and advanced, depending on the asset class considered

- LGD floors for the Advanced approach

- for unsecured exposures fixed, based on the asset class

- for secured exposures, depending on the nature of the collateral

- EaD floors for the Advanced approach

- function of the on-balance and off-balance sheet exposures using the applicable Credit Conversion Factor (CCF) in the Standardised approach

Removal of the advanced IRB approach altogether

In situations where the quantity and quality of the relevant data available are insufficient (e.g. low-default portfolios) or where the institution has no access to the data specific to its portfolio which is not already public (e.g. behavioural data of a given counterparty) or where the modelling techniques lack robustness or stability, the advanced IRB approach can no longer be used.

It has been translated in the new Basel framework by the removal of the advanced IRB approach for exposures to banks, other financial institutions, large and mid-sized companies (consolidated revenues greater than EUR 500 M) as well as all equities.

For all but equities, the institutions are advised to use (with the approval of supervisors) the foundation approach; for equities, the Standardised Approach is the only one permitted. If there has been no explicit refusal from Regulators to allow institutions to fall back to the standard approach, however, suspicion is quite strong that this would be a very dangerous road to travel and therefore, waiting for someone else to try would be prudent.

It has to be noted that, given the more stringent demands on the institutions using the IRB approach, as well as the new output floors, the 1.06 scaling factor that is applied to RWAs determined by the IRB approach to credit risk, has been removed - a mean silver lining for most institutions.

Market Risk - Fundamental Review of the Trading Book (FRTB)

The revised capital standards for market risk, better known as Fundamental Review of the Trading Book, were laid down in the ‘Minimum Capital Requirements for Market Risk’ document, published by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision in January 2016. The FRTB was to replace the previous framework as from 2019, but owing to the pivotal release of Basel III: Finalising post-crisis reforms document in December 2017, its implementation may be postponed to as far as 2022.

Why were these standards developed?

The FRTB addresses structural shortcomings in the market risk framework that were exposed in the course of the financial crisis.

- Trading book exposures were undercapitalised due to a very subjective trading book criterion and regulatory arbitrage through switching between books.

- The VaR-based framework proved to inadequately capture illiquidity and credit risk, and created incentives for banks to take on tail risks.

- The assumption that hedging and diversification have risk-reducing benefits under stressed market conditions could not be maintained.

- Given that the Standardised Approach (SA) was not risk-sensitive enough and suited neither for complex instruments nor for capturing hedging and diversification, there was no credible threat of an Internal Models Approach (IMA) withdrawal.

In short, the previous market risk frameworks failed to ensure comprehensive risk capture. As a first reaction, in 2009, the regulators adopted the so-called Basel 2.5 framework to add:

- A capital charge against default risk and ratings migration risk,

- A stressed VaR (sVaR),

- Minor amendments on the boundary between the trading and the banking book and

- Rules for the securitisation exposures to be treated as held in the banking book.

These changes proved to be insufficient to ensure financial stability and solid capitalisation. The BCBS therefore conducted a fundamental review of the market risk framework addressing its structural deficiencies with three consultative papers and four quantitative impact studies.

The Fundamental Changes

After the minor changes introduced in Basel 2.5, the FRTB is indeed a fundamental revision focusing on three major elements:

- A revision of the boundary between trading book and banking book

- A revision of the Standardised Approach

- A revision of the Internal Models Approach

The capital requirements have to be met on a continuous basis, limiting the possibility of window-dressing.

The Revised Boundary Between Books

Addressing common practices of regulatory arbitrage, the FRTB firmly restrains the allocation of instruments between the trading and the banking books. For this purpose, the new standard assigns specific instruments to the banking book and trading book respectively. Deviations from these lists are only possible when explicitly allowed by the supervisor. Switching instruments between books is strictly prohibited. Re-designation is limited to exceptional circumstances, irrevocable and conditional upon supervisory approval. Should the capital charge be reduced by such exceptional switching, the difference in capital is imposed as an additional Pillar I charge.

The Revised Standardised Approach (SA)

The SA methodology was substantially modified in order to create a common risk data infrastructure. It is intended to be suitable for banks with limited trading activity and the more advanced IMA-users at the same time. Every bank is obligated to calculate the SA, including those using IMA, for which it serves as a risk-sensitive fall-back and floor. Moreover, all securitisation instruments must be addressed with the SA.

The new SA capital charge is a simple sum of three components:

- A sensitivities-based capital charge based on delta, vega and curvature risks. Instruments are first mapped to an extended set of risk factors. Risk-weighted sensitivities are then aggregated within buckets and risk classes based on prescribed formulas with specified correlations. The aggregate capital charge is the simple sum of risk-level charges. Finally, the largest of the three correlation-scenarios determines the ultimate portfolio level risk capital charge. This procedure is applied independently for delta and vega risks, while the curvature risk is based on two stress scenarios and only partially acknowledges hedging benefits.

- The standardised Default Risk Charge (DRC) is an independent capital charge intending to capture stress events in the tail. The jump-todefault (JTD) risk of each instrument is computed as a function of the notional amount (or face value), market value and prescribed LGD. The net JTD risk positions are determined according to offsetting rules, allocated to buckets and weighted. The total DRC for non-securitisations is a simple sum of bucket-level charges.

- A residual risk add-on captures any risk beyond the main risk factors. It is the simple sum of the gross notional amounts of all instruments bearing residual risks, multiplied by a risk weight of 1.0% for instruments with an exotic underlying and a risk weight of 0.1% for instruments bearing other residual risks. The supervisor can address any potentially under-capitalised risk by imposing an additional capital charge under Pillar 2.

In addition to this, in January 2016, the BCBS released the minimal capital requirements. Those are tailored for small institutions for which the implementation of the Revised Standardised Approach would be just too unwieldy. This is particularly useful for the European environment, as EU institutions tend to include even much smaller, non-globally active banks among the institutions that need to comply with Basel.

The minimal capital requirements are very analogous to what a standardized approach was in the past, as they:

- Remove capital requirements for vega and curvature risks

- Simplify the basis of risk calculation

- Reduce the risk factor granularity and the correlation scenarios to be applied in the associated calculations

Whilst former proposals of CRR 2 and CRD V had thresholds to specify what sort of institutions may benefit from this approach, the current release of the new Basel III related documents makes these proposals obsolete.

The Revised Internal Models Approach (IMA)

The IMA is revised on three broad issues in terms of methodology and conditionality:

- More granular model approval: The use of the IMA is strictly conditional upon the explicit approval by the supervisor at trading desk level. Minimum conditions are for example a conceptually sound risk management system, an independent model validation and a stress testing programme. The desk approval is based on daily P&L attribution tests and backtesting.

- More coherent and comprehensive risk capture of illiquidity and tail risk: Risk calculation is based on the Expected Shortfall (ES) metric calibrated to a 12-month period of significant financial market stress. It can be computed with a reduced set of bank-selected risk factors if these explain at least 75% of the variation in the ES model. The calculation is based on varying liquidity horizons and distinguishes modellable risk factors from non-modellable risk factors (NMRFs). The modellability of risk factors has to be proven through strict data availability and quality criteria. Non-modellability is penalised with separate stressed capital add-ons for NMRFs.

- Constraints on the capital-reducing effects of hedging and portfolio diversification: The Incremental Risk Charge (IRC) is replaced by a Default Risk Charge (DRC) model.

This VaR model capturing default risks does not allow diversification with other market risks.

Implications of the FRTB

Given the fundamental nature of the review, the impact on banks will be considerable. The main challenges arise in the following four domains:

- An internal reorganisation is necessary to adapt internal processes, policies and organisational structures, with possibly a shift in the centre of gravity from the Finance to the Risk Management department.

- A considerable amount of data has to be collected to demonstrate the modellability of the risk factors. Based on these steps, the actual calculations have to be conducted and the capital optimisa¬tion updated. The complexity of the new models will increase processing times. Nevertheless, the capital requirements will have to be met at the close of each business day.

- In addition, the mandatory calculation of the standardised model should not be underestimated, since the modification of the SA as a credible fall-back made it necessarily more complex.

- Finally, the resulting capital charge is expected to increase, naturally impacting business models and strategies. Impact studies by the BCBS and other sources diverge considerably. Yet, studies concur with an overall increase, and a BCBS paper estimates that the median bank will face an increase of 22% in total market risk capital requirements.

The burden of the regulatory compliance added by the FRTB is hence twofold:

- Capital charges are expected to increase, and

- Operational costs will be rising.

The two above-mentioned points therefore question the benefit of maintaining the IMA process as such.

Interest Rate Risk - Interest Rate Risk in the Banking Book (IRRBB)

Banks’ capital and earnings are largely exposed to the variation of interest rates (IR). In today’s persistently rock-bottom IR environment, the sensitivity of banks’ core business to fluctuations in IR is particularly evident. This particular business environment as well as the revelation of IR vulnerabilities during the financial crisis have led to policy efforts to improve and standardise IR management.

In April 2016, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) published a revised standard on the Interest Rate Risk in the Banking Book (IRRBB). It replaces the previous Principles for the Management and Supervision of Interest Rate Risk from 2004 and is part of the Basel III reform. As an element of the Basel Pillar 2 framework, it defines international standards for the identification, measurement, monitoring and control of IR risk. In comparison to the previous principles, it gives more specific guidance for IR management, provides an updated standardised framework, sets extended disclosure requirements, and defines a stricter outlier test.

The following text provides a short discussion on IR management, a brief overview of the new requirements and an outlook into arising implementation challenges.

Interest Rate Risk

The BCBS defines IR risk in the banking book as the “current or prospective risk to the bank’s capital and earnings arising from adverse movements in interest rates that affect the bank’s banking book positions”1 . IR risk can arise for various reasons.

For example, changes in the slope and the shape of the yield curve in the presence of a timing mismatch in the instrument’s maturities (gap risk) or relative changes in IR for financial instruments that have similar tenors but are priced using different IR indices (basis risk). IR risk can also arise from option derivatives or embedded options, including situations where the behaviour of clients - e.g. in terms of prepayment or deposit withdrawal – may adjust to IR changes (option risk).

1 §8-9 of the IRRBB

Such risks are inherent to maturity transformation, i.e. the core activity of banks. In order to avoid a threat to the current capital base or future earnings, IR risk must be managed appropriately. The measurement of IR risk can be approached in two ways: economic value (EV) or expected earnings (EE). Stabilising earnings and stabilising the economic value may appear as conflicting goals. The longer the duration of a new transaction, the stronger the stabilising effect on earnings, but the greater the impact on EV under stress. The BCBS Standards re-emphasise the importance of measuring IR risk along both dimensions.

Regulation of IR Risk Management

To date, the management of IR risk in the banking book is regulated by the BCBS ‘Principles for the management and supervision of interest rate risk’. At EU level, these rules are laid down in the Capital Requirements Directive and Regulation (CRD IV and CRR)2 . In the framework of the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP), authorities control banks’ management of IR risks. Supervisors order correcting measures according to a standard shock, when a bank’s EV declines by more than 20% of their own funds as a result of a sudden and unexpected change in interest rates of +/-200 basis points. The 2015 ‘Guidelines on the management of IR risk arising from non-trading activities’ from the European Banking Authority (EBA) specify the details of the European rules.

Similar to the previous Principles, the BCBS Standards rule that all banks have to be familiar with IR risk, to adequately identify their exposures and to measure, monitor and control the risk3 . After the proposition of a Pillar 1 approach was rejected by stakeholders in consultations, the BCBS chose an enhanced Pillar 2 approach. The IRRBB is hence part of the Supervisory Review Process. The new standard consists of 12 principles, nine of which addressed to banks and three to supervisors. Key highlights include:

- Governance: The BCBS Standards declare the responsibility for IR risk management and the definition of risk appetite to lie with the governing body of the bank. It can be delegated to senior management, experts and ALM committees, but governing bodies have to be informed about the outcomes and implement internal controls.

- Measurement and modelling: IR risk has to be assessed using both EV and EE. The measures have to be based on accurate data and tested for robustness with different shock scenarios and stress tests. In reaction to the vulnerabilities displayed in the financial crisis, the BCBS Standards underline the importance of understanding and testing modelling assumptions. Furthermore, banks have to monitor the related credit spread risk in the banking book (CSRBB) as well.

- Enhanced disclosure requirements: The new standard disclosure requirements go beyond those of the previous principles. They require the publication of EV and EE in six scenarios as well as far-reaching qualitative information on the bank’s IR risk governance and modelling framework.

- Supervisory review: IR risk continues to be part of the Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process (ICAAP). The BCBS Standards elaborate on the terms and conditions of supervisory review. The standardized framework has been enhanced (see below). With the permission of their regulator, banks may use their internal models to measure IRRBB and assess the impact of the six prescribed scenarios. Supervisors should require mitigating actions or additional capital when the risk is excessive or when the IRRBB management is inadequate.

- Outlier test: Supervisors should identify “outlier banks” subject to stricter thresholds. The BCBS Standards modify the current 20% of Tier 1 plus Tier 2 threshold to 15% of Tier 1. They also enlarge the number of scenarios under which capital depletion is calculated from two to six (parallel up, parallel down, steepener, flattener, short rate up and short rate down).

2 CRD IV Art. 84 & 98(5), CRR Art. 447 & 448

3 §13 of the IRRBB

The Standardised Framework

One major novelty of the IRRBB is the revised standardised framework for IR risk. Banks can choose to adopt this simplified approach or be obliged to use it as a fall-back when their internal model is insufficient. Only Economic Value measurements fall in its scope. Key highlights are as follows:

- Deterministic cash flows should be slotted across 19 time buckets based on their maturity (fixed rate) or their repricing date (floating rate).

- Automatic interest rate options (either explicit as in cap/floors or embedded) are subject to full-revaluation with a relative increase of 25% in the implicit volatility for the six standard scenarios.

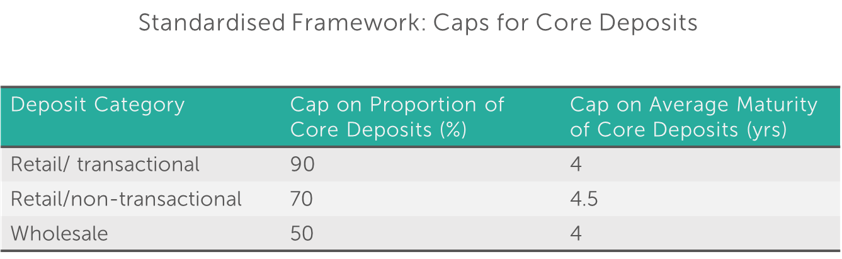

- Non-maturity deposits (NMDs) are segmented into retail and wholesale categories and split between core and non-core deposits (using observed volume changes over the past 10 years). Caps apply on the proportion of core deposits. Non-core deposits are considered as overnight positions. Banks should define slotting procedures for core deposits subject to maturity caps.

- Prepayment and early redemption: defining the baseline prepayment rate and the redemption ratio remains the responsibility of the bank. However, the standard framework defines the multipliers that should be applied under each of the six prescribed scenarios.

Challenges in IRRBB Implementation

An adequate and timely implementation of the IRRBB is indispensable, because supervisors will have the power to sanction non-compliance. Authorities can impose additional own funds, request divestment, require reduction of risk, prohibit distributions to shareholders or demand additional disclosure.

The enhancement of the IRRBB measurement system will pose a first challenge. Although the EBA guidelines have raised the bar significantly in the past, banks may see the need to invest in more granular and robust modelling. More efficient engines may prove helpful to run EV and EE projections under many scenarios over a multiyear time horizon. To the least, banks should be able to run economic value and net interest income simulations under the six new scenarios.

The enhancement of the governance framework is likely to be a second important challenge. A strong governance is key in keeping model risk under control by ensuring that assumptions (e.g. regarding the behaviour of borrowers and depositors in the face of IR movements) are validated, reviewed regularly, back-tested, stress tested and properly documented. The new disclosure requirement will ensure that these tasks receive a heightened focus. Governance will also need to grow to the challenge of disclosing the bank’s overall IRRBB management and mitigation strategies (e.g. limits setting, hedging practices, conducts of stress testing, etc.).

| Scenarios | Multiplier on Prepayment Rate | Multiplier on Early Redemption Ratio |

| Parallel Up | 0.8 | 1.2 |

| Parallel Down | 1.2 | 0.8 |

| Steepener | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Flattener | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Short Rate Up | 0.8 | 1.2 |

| Short Rate Down | 1.2 | 0.8 |

IRRBB Application in the EU

The IRRBB standards are yet to be translated into the EU law, but will come into effect before January 2022. In November 2016, the European Commission made a proposal, counting on January 2018 as the deadline - plans that were hampered by the aforementioned December 2017 BCBS document. As there is substantially more to translate into European legislature, no concrete proposal has been released to the public at the time of writing.

In a not too distant future, we should expect to see a proposal that amends the CRD IV and the CRR1 to include revised Basel IV standards, such as the Fundamental Review of the Trading Book (FRTB) and the IRRBB. It will adopt the revised IRRBB disclosure rules, the measurement in both EV of equity and EE, the new standardised framework and the stricter outlier test. It is likely that the EU proposal will foresee exemptions for small banks and a phase-in period.

Once the CRD V and CRR II are adopted, the EBA will update its guidelines accordingly. It will detail the standardised framework and define the six shock scenarios applied to IR. The implementation of these detailed standards will then follow a very tight timeline.

Implications of the FRTB

The design of risk policies, analysis of balance sheet dynamics, control of risk data and model validation can be a challenging and time consuming endeavour. Finalyse can bring added value by helping you to identify the IRRBB risks, assess potential gaps and design measurement and monitoring solutions. In addition, Finalyse can support you with the automation of risk processes, the implementation of effective internal controls and the design of management information systems.

1 CRD IV Art. 84 & 98, CRR Art. 448

Finalyse InsuranceFinalyse offers specialized consulting for insurance and pension sectors, focusing on risk management, actuarial modeling, and regulatory compliance. Their services include Solvency II support, IFRS 17 implementation, and climate risk assessments, ensuring robust frameworks and regulatory alignment for institutions. |

Trending Services

Risk Data Analyser

#Regtech

#DigitalTransformation

Risk Appetite Framework for Insurance

#RiskAppetite

#InsuranceRisk

IFRS 17 implementation

#IFRS17

#InsuranceAccounting

Finalyse BankingFinalyse leverages 35+ years of banking expertise to guide you through regulatory challenges with tailored risk solutions. |

Trending Services

AI Fairness Assessment

#ResponsibleAI

#AIFairnessAssessment

CRR3 Validation Toolkit

#CRR3Validation

#RWAStandardizedApproach

FRTB

#FRTBCompliance

#MarketRiskManagement

Finalyse ValuationValuing complex products is both costly and demanding, requiring quality data, advanced models, and expert support. Finalyse Valuation Services are tailored to client needs, ensuring transparency and ongoing collaboration. Our experts analyse and reconcile counterparty prices to explain and document any differences. |

Trending Services

Independent valuation of OTC and structured products

#IndependentValuation

#StructuredProductsValuation

Value at Risk (VaR) Calculation Service

#VaRCalculation

#RiskManagementOutsourcing

EMIR and SFTR Reporting Services

#EMIRSFTRReporting

#SecuritiesFinancingRegulation

Finalyse PublicationsDiscover Finalyse writings, written for you by our experienced consultants, read whitepapers, our RegBrief and blog articles to stay ahead of the trends in the Banking, Insurance and Managed Services world |

Blog

Finalyse’s take on risk-mitigation techniques and the regulatory requirements that they address

Regulatory Brief

A regularly updated catalogue of key financial policy changes, focusing on risk management, reporting, governance, accounting, and trading

Materials

Read Finalyse whitepapers and research materials on trending subjects

Latest Blog Articles

Contents of a Recovery Plan: What European Insurers Can Learn From the Irish Experience (Part 2 of 2)

Contents of a Recovery Plan: What European Insurers Can Learn From the Irish Experience (Part 1 of 2)

Rethinking 'Risk-Free': Managing the Hidden Risks in Long- and Short-Term Insurance Liabilities

About FinalyseOur aim is to support our clients incorporating changes and innovations in valuation, risk and compliance. We share the ambition to contribute to a sustainable and resilient financial system. Facing these extraordinary challenges is what drives us every day. |

Finalyse CareersUnlock your potential with Finalyse: as risk management pioneers with over 35 years of experience, we provide advisory services and empower clients in making informed decisions. Our mission is to support them in adapting to changes and innovations, contributing to a sustainable and resilient financial system. |

Our Team

Get to know our diverse and multicultural teams, committed to bring new ideas

Why Finalyse

We combine growing fintech expertise, ownership, and a passion for tailored solutions to make a real impact

Career Path

Discover our three business lines and the expert teams delivering smart, reliable support